It has proven surprisingly difficult to explain regional variations in Covid-19 prevalence. Whenever you find one factor that seems important, a counterexample crops up.

Vietnam is one of the big success stories, with the nation of 97 million people not having reported a single fatality. Even if a few cases were missed, that’s pretty impressive.

But the explanation for that success is over-determined. A young population? Tropical weather? BCG vaccine? Effective test/trace/isolate? Mask wearing? Less obesity? Luck?

The Economist has a new article that discusses two success stories, Vietnam and the southern Indian state of Kerala:

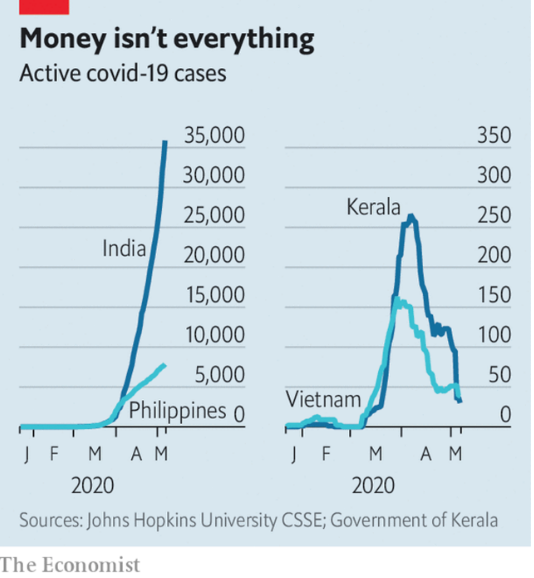

Kerala was the first place in India to be impacted, and its caseload soared in March. But as India’s caseload continued rising rapidly higher, Kerala’s peaked and then began declining sharply. Why?

Like Vietnam, Kerala has a young population, BCG vaccination, and a tropical climate. But so does India! That’s what makes the Kerala story interesting. At the very least, it suggests that public policy (or at least culture) plays an important role:

Kerala’s state government has been similarly energetic, from the chief minister, its top elected official, giving nightly pep talks to village-level committees working to set up public hand-washing stations. Aside from showing logistical efficiency in monitoring cases and equipping its health system, it has also emphasised sympathy and compassion for people affected by the pandemic. The state has mobilised some 16,000 teams to man call centres and to look after as many as 100,000 quarantined people, ensuring they do not lack food, medical care or simply someone to talk to. Free meals have been delivered to thousands of homes, as well as to migrant workers stranded by a national lockdown.

Both Kerala and Vietnam are keenly aware that the danger is far from over. Until there is a vaccine or better treatment, Vietnam will remain on alert, says Mr Pollack. Kerala, for its part, is preparing for a huge influx of expatriate workers returning from the economically battered Arab Gulf countries. More than 300,000 have requested help getting home via a state website.

This last point is important. Migrant workers in places like Singapore and the Gulf have been hit hard by the Covid-19 epidemic, so Kerala is certainly not out of the woods.

Nonetheless, the Kerala example suggests that any explanation of Covid-19 prevalence is likely to be complicated. It’s not that age, climate, and BCG vaccines don’t matter, but lots of other things matter too.

Kerala is not a particularly prosperous place, but it does have India’s highest “Human Development Index“, which looks at things like health, education, extreme poverty, etc. On the other hand, hard hit places like Sweden and Belgium also do well with this index. It’s complicated.

Kerala is what Americans would call a “blue state”. But I wouldn’t make too much of that either, as in America itself many of the blue states have been among the hardest hit. It’s complicated.

But at least Kerala makes things a bit less complicated. It’s not like nothing can be done in a country such as India. There are things that work. Whether other states have the required “state capacity” is another question, but at least we know there are some things that matter.