Tyler Cowen has a post on the problems encountered by Republican tax cutters at the state level. The post focused on Kansas and Louisiana, which were both recently forced to raise “revenues” to cover budget shortfalls. I decided to take a broader look at the states, and to focus on the sine qua non of supply-side economics, reducing the top income tax rate.

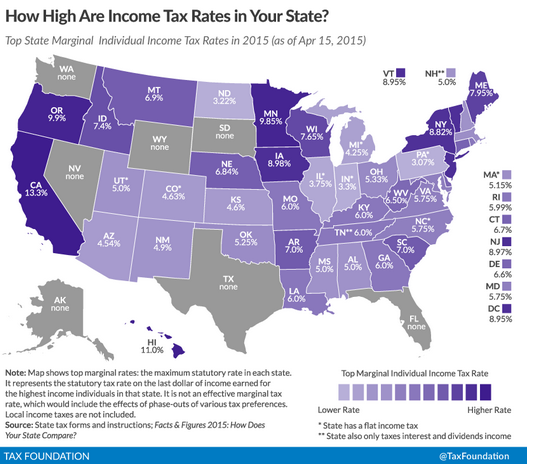

I found that between 2010 and 2015, 19 states changed their top income tax rate, with 5 increases and 14 reductions. So it’s not just Kansas and Louisiana. Even more surprising, Louisiana was not one of the 14, its top rate remains at 6%, a bit above average for states:

So what happened in Louisiana, I thought Bobby Jindal was a supply-sider? Inertia happened. Here’s Bruce Bartlett:

So what happened in Louisiana, I thought Bobby Jindal was a supply-sider? Inertia happened. Here’s Bruce Bartlett:

In January, Gov. Jindal proposed a tax reform that conformed to the Republican ideal, which he hoped would make him a contender for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination. It would have completely eliminated the state’s corporate and individual incomes taxes, replacing the revenue with an increase in the state sales tax to 7 percent from 4 percent.

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a liberal think tank, charged that the Jindal plan would raise taxes on the bottom 80 percent of Louisiana citizens. Conservative tax guru Grover Norquist of Americans for Tax Reform cheered the Jindal plan, calling it “the gold standard for pro-growth reform.”

But the Jindal plan was not received well, even in conservative Louisiana. An April 2 poll from Southern Media & Opinion Research found a sharp drop in Jindal’s popularity to 38 percent from 51 percent in October. His tax reform was opposed by 63 percent of Louisianans and supported by just 27 percent. Even among Republicans, fewer than half supported the Jindal tax plan.

On April 8, Jindal admitted defeat and withdrew his tax reform. Bloomberg’s Josh Barro said that Jindal had overreached, noting that over the last 50 years only one state, Alaska, had abolished a major state tax, which oil revenue allowed it to do.

It’s not that a tax regime with no income tax is politically infeasible; you see that in a number of other states. The problem is getting from here to there. Potential losers will squawk more loudly than gainers.

So in one of the 14 states that cut the top rate (Kansas) the policy failed, while the other 13 are . . . not discussed by the New York Times. Some of the tax cuts were small, with the largest being:

Rhode Island, down from 9.9% to 5.99% (why not 5.999%?)

North Carolina, down from 7.75% to 5.75%

Kansas, down from 6.45% to 4.6%

North Dakota, down from 4.86% to 3.22%

Oregon, down from 11.0% to 9.9%

Ohio, down from 5.925% to 5.33%

It’s worth noting that top rates were cut in some very liberal states like New York and Massachusetts, but only by small amounts. Among the 5 increases, the two notable cases were California and Minnesota, both of which were enacted for “progressive” reasons, and both of which seem (so far) to be fairly successful.

Let’s return to the “inertia” problem, and try to figure out the strange map above. It makes sense that liberal states would have high taxes, but why some more than others? Why no income tax in Washington State, and a top rate in Massachusetts that is lower than in many southern states? And why the 14 states seeing recent cuts in top rates? I think there are clear answers to these questions, but we need to consider several factors:

1. Voters don’t like high income tax rates. In both Washington (state) and Massachusetts, voters rejected referenda proposals calling for progressive income taxes, by wide margins. Even more shocking, in 2002 about 45% of Massachusetts voters voted to entirely eliminate the state income tax. Even the Republicans opposed that initiative. I recall a colleague told me about a taxi ride where the driver said; “like, I don’t get it. Why would anyone not vote to eliminate the income tax.” If the driver came from somewhere like Somalia, then it’s not hard to understand why there might be a disconnect between taxes paid and perceived benefits received. I was born here and even I don’t see much connection. My town spent $200 million replacing a perfectly good high school built in the 1970s. Why?

2. High income tax rates are more feasible where you have a captive audience. I hope I don’t need to explain California. (I plan to retire there rather than (low tax) Austin or Miami.) And the New York area has cultural amenities. But what about frigid Minnesota? Here’s what non-Midwesterners may not know. If you are a highly educated “Millennial,” and like cities like Seattle, Portland, Austin, Boston or Raleigh, there’s really only one place in the Midwest that would work for you—Minneapolis/St. Paul. Governor Walker keeps getting hammered because Wisconsin is not doing as well as Minnesota, but there’s not much he can do to keep well-educated UW grads (who want to stay in the Midwest) from moving to the Twin Cities. I’m not saying their tax increase will work in the long run, but it will work in Minnesota better than in any other Midwestern state.

3. Tax rates have lagged far behind political change. During my lifetime, many red states have gone blue, and vice versa. California’s recent tax increases reflect this fact, as do the many tax cuts in states that have become more red. I predict that South Carolina will have to cut its top rate at some point, now that it has the highest taxes in the South. It’s odd that many (blue) rust belt states have (for historical reasons) lower top rates than many conservative southern and western states. That will gradually change.

4. Don’t let the NYT tell you what is “popular.” I’ve already mentioned the opposition of liberal Washington and Massachusetts voters to a progressive income tax. I might add that although Governor Brownback is extremely unpopular among Republican legislators, it’s not clear that this applies to voters. Before the election last fall there was a flurry of articles telling us about how unpopular Brownback was with the voters. I expected a whole slew of follow up articles after he lost the election. But something kind of strange happened, he won. And those follow-up articles? I didn’t see them. Maybe Kansas voters liked the tax cuts.

5. On the other hand there’s no way to hide the fact that Brownback did screw up—his policies performed poorly. He cut the top rate, eliminated taxes on small business, and did little to cut spending. The result was predictable—suddenly everyone and his brother declared “I’m a small business.” and revenues plummeted. A deficit opened up, leading to the recent (regressive) tax increases. But even today Kansas has a tax regime that is more progressive than the regime in Massachusetts. And spending in Kansas is higher than in the other Great Plains states. A much better example is North Carolina, which slashed its top rate, and also cut other programs such as unemployment insurance, to avoid running deficits. Unlike Kansas, North Carolina is doing well, although in fairness it’s been doing well for decades. It’s hard to draw conclusions because most state level changes are small, and the effects show up very gradually. That’s why I prefer a cross sectional approach, and on balance that approach does suggest that people prefer states with no income tax. On average they vote that way with their feet, and in the case of Washington State, also at the ballot box.

Progressives can take heart from the fact that (in my view) the supply-side argument for lower top rates will gradually weaken over time. In the new economy firms have tremendous pricing power, and states have more taxing power than in the old commodity-driven economy. In the old days high taxes would make people and companies move to other states. Commodity industries are highly competitive on price. That’s Kansas and Louisiana. But the new economy in places like Manhattan and Boston and DC and Silicon Valley has companies with lots of market power, and people so rich they care more about amenities than a few extra bucks. So that works in favor of the progressives, but not yet in all 50 states.