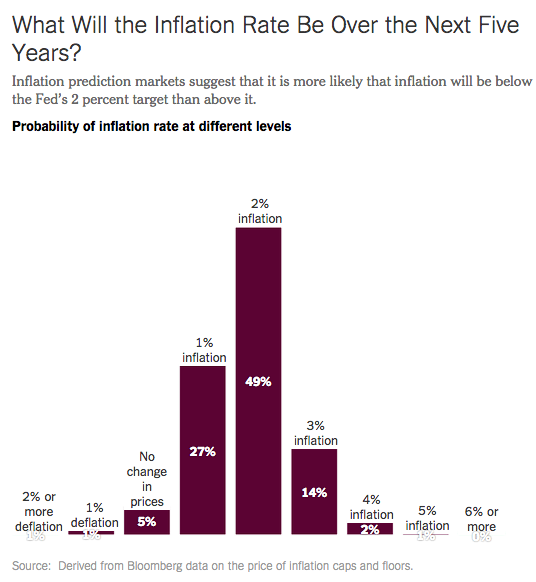

Justin Wolfers has a good piece in the NYT, with a graph showing the current values of some inflation derivatives:

The numbers actually represent ranges. Thus the 49% chance of 2% inflation means that there is a roughly 49% chance of inflation between 1.5% and 2.5%.

The numbers actually represent ranges. Thus the 49% chance of 2% inflation means that there is a roughly 49% chance of inflation between 1.5% and 2.5%.

If we assume a bell-shaped distribution, I’d guess the median inflation estimate is around 1.75% or a bit more. In that case there’s roughly a 66% chance that inflation will undershoot 2% over the next 5 years. But keep in mind that this is a CPI inflation prediction market. And the Fed actually targets PCE inflation, which runs about 0.35% below CPI inflation. So the market currently expects about 1.4% PCE inflation over the next 5 years. Alternatively, there is an 80% chance that inflation will undershoot the Fed’s PCE target over the next 5 years.

Does that mean money is too tight? Not necessarily, as the Fed has a dual mandate, and employment is likely to be above average over the next 5 years (albeit only because the previous 6 were so horrible.) Nonetheless, I’d guess that dual mandate considerations would call for no less than about 1.8% PCE inflation over the next 5 years.

Even worse, the dual mandate defense of the Fed implies they should have had inflation run above target during the high unemployment years, and of course they’ve done exactly the opposite. So if you take the Fed’s unwillingness to run a countercyclical inflation rate into account, the current situation is even more indefensible.

Even worse, the Fed seems unaware of the fact that the current policy regime is broken, and needs to be replaced before we again slide to zero interest rates in the next recession. Reading the 2009 transcripts, (which just came out) was a sobering experience. The Fed pats itself on the back when it produces stable NGDP growth (as in the Great Moderation), or 2% inflation since 1990. But when they screw up and produce a macroeconomic disaster, they discuss the situation as if it’s not their job to steer the nominal economy. Bad things just sort of happened. It reminds me of the transcripts from late 1937, when the Fed was unwilling to accept the fact that the higher reserve requirements (which raised interest rates by 25 basis points) contributed to the double dip depression, even though the policy was enacted to prevent inflation, and that can only be done by restraining AD. (BTW, I’ve complained about this asymmetry for years, as has Christy Romer, and as did Milton Friedman many decades ago.)

I haven’t even come close to reading all the minutes; if any of you have more time than I do see if there is any soul searching about the foolish decision to not cut interest rates in the meeting after Lehman failed. Or regret over the decision instituting a contractionary IOR policy in October 2008. I was especially disappointed with Bernanke’s support for ending QE1 in late 2009, partly on the grounds that further purchases ran the risk of leading to excessive inflation.

Vaidas Urba directed me to this Bernanke comment from the April 2009 meeting:

The other perspective, however, which I think is very important and a number of people pointed out, is the medium-term constraints and dynamics that affect the economy. Unfortunately, our economy still has a significant number of very serious imbalances that need to be resolved before it can grow at a healthy pace. Just to list five. First, the leverage issue of both the financial and the household sectors. Second, wealth–income ratios are well below normal, and therefore more saving is needed to rebuild those ratios. Third, we have dramatic fiscal imbalances, which have to be reconciled at some point. Fourth, we have current account imbalances, which are at least temporarily down, but the Greenbook forecast for the medium term is that there is probably some worsening in that dimension. And fifth, as a number of people mentioned, the unemployment we are seeing is probably not mostly a temporary-layoff type of unemployment. There is a lot of reallocation going on. The financial and the construction sectors are probably not going to be as big in the future as they have been recently, so there will need to be that readjustment across sectors.

If you put all of those imbalances together and you think about what is going to support sustainable economic growth, it is a little hard to see where a robust recovery is going to come from.

How about from the Fed?

Seriously, whenever you are in a deep global slump it NEVER looks like the various components are likely to generate growth. Why would hard up people fearing job loss consume more? Who will we export too? Why would firms invest when sales are slow? That was even more true in April 1933, when FDR devalued the dollar and caused industrial production to rise by 57% in 4 months. And it was true in December 1982, right before NGDP grew at an 11% rate over 6 quarters.

In retrospect it is obvious the economy needed more NGDP in 2009, and that the Fed needed to make it happen. But they didn’t see it.

PS. Not to pick on Jeffrey Fuhrer, who is a fine economist, but this seems slightly off the mark:

The US inflation rate is about 1.5 percent a year, below the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. Too-low inflation, Fuhrer said, indicates that not all factories and businesses are humming, and more people are unemployed.

“It’s just a symptom of a poorly functioning economy that’s under capacity,” he said.

Here are some things to consider:

1. Fuhrer is an executive vice president and senior policy adviser to Boston Fed president Eric Rosengren.

2. The Fed is targeting inflation at 2%.

3. The Fed is very likely to raise interest rates in the near future, which (in theory) suggests that inflation is either where they want it, or a bit too high.

Instead of saying 1.5% inflation is a “symptom of a poorly functioning economy” I’d rather he say it’s a symptom of a poorly functioning monetary regime.

PPS. I was asked about slowing NGDP growth in Australia. From the NGDP numbers it seems like policy is a bit too tight, but then one must also consider distortions caused by commodity price swings. However Rajat sent me the following:

Australian workers, used to fairly solid wages rise each year for the past two decades, are faced with an economy unable to deliver the types of increases many expect.

. . .

The ABS reported that wages grew 0.6%, as expected but this left year on year growth at just 2.5% for 2014.

That’s only a slight dip on the recent 2.6% yoy growth rate but 2.5% is a fresh low for this wage price index series which dates back to 1997.

I’m reluctant to criticize the excellent RBA, but they do need to ease policy a bit.

PPPS. The Boston Globe also said this about Fuhrer:

Fuhrer, a father of three adult children, lives with his wife in a historic farmhouse in Littleton. He also participates in Revolutionary War battle reenactments as a member of the Boxborough Minutemen, where he learned to play the fife.

Don’t raise rates until you see the whites of inflation’s eyes.