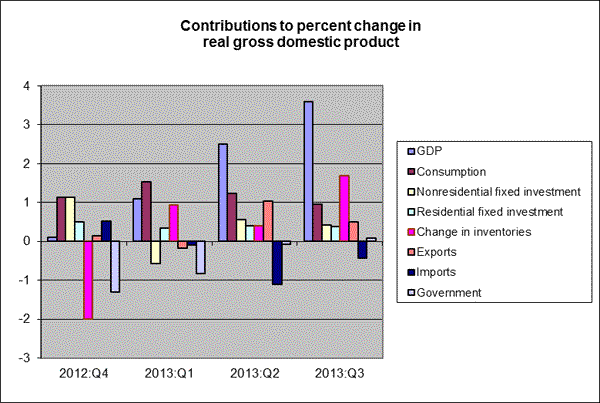

On Thursday the BEA announced its revised estimate of U.S. real GDP. The initial estimate had been that the economy grew at a 2.8% annual rate in Q3, but that has now been revised up to 3.6%. Unfortunately, most of the gain came in the form of more inventory accumulation. Fourth-quarter production was higher than originally estimated, but final sales are now claimed to have grown at only a 1.9% annual rate, a little weaker than the original 2.0% estimate.

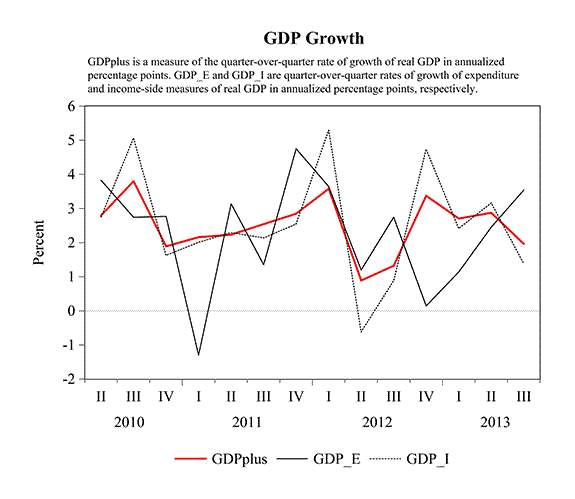

Moreover, the added detail in the new release gives us the first look at a second way to estimate overall growth. We usually calculate GDP by adding up expenditures on all domestically produced final goods and services. In principle, we should be able to arrive at the same magnitude by adding up the incomes earned by all Americans. In practice, when the BEA collects data from different sources, the estimates turn out to be different, and the difference between the expenditure-based estimate and the income-based estimate is simply described as a “statistical discrepancy.” Since we don’t have a good theory for what the statistical discrepancy represents, it’s a good idea to look at both measures. While the expenditures-based measure (the one officially reported) registered real GDP growth of 3.6%, the income-based measure suggests growth was in fact only 1.4%.

One approach is simply to use an average of the two estimates, namely, to conclude that GDP (even including the inventory accumulation) only grew by 2.5% during the third quarter. Some new research by Aruoba, Diebold, Nalewaik, Schorfheide, and Song (2013) proposes something a little more sophisticated. Their inference of true GDP growth (which they call “GDPplus”) is plotted as the red line in the graph below. This tends to track the income-based GDP measure (dotted line) more closely than the expenditure-based measure (solid line), and estimates U.S. real GDP growth to have been about 2.0% for Q3.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

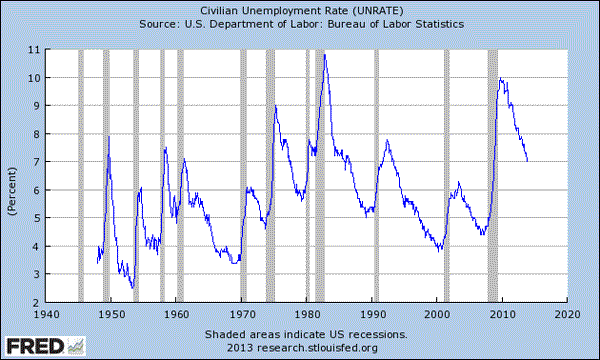

Despite the sluggish growth of real final sales, the labor market continues to improve. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported on Friday that nonfarm establishments added 203,000 workers on a seasonally adjusted basis in November, and have averaged almost as much over the last year. Job growth was enough to bring the estimated unemployment rate (based on the BLS’s separate survey of households) down to 7.0%. While still quite high by historical standards, a 7% unemployment rate is back within the range of values that have characterized other extended episodes in recent U.S. history. For example, unemployment was 7% or higher from December 1974 through June 1977 (a period when the year-over-year PCE inflation rate averaged 7.0%) and also from May 1980 to December 1985 (with an average inflation rate of 5.5%). There is nevertheless clearly still a lot of slack in the U.S. economy, with PCE inflation over the last year of only 0.7%.

Source: FRED.

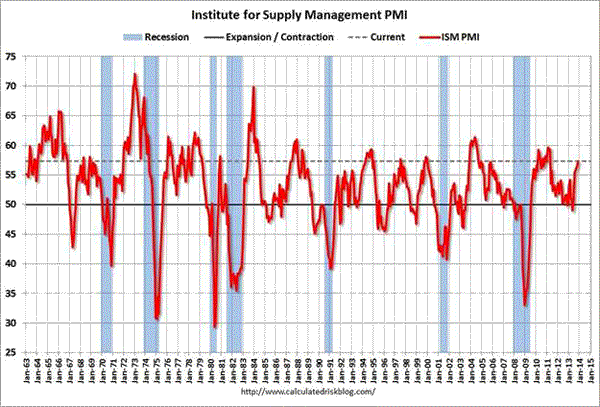

But there have been some other indicators that are unambiguously positive. The Institute for Supply Management released a value for their manufacturing PMI that was up to 57.3, an unusually high value for that indicator indicating widespread reports of improving business conditions.

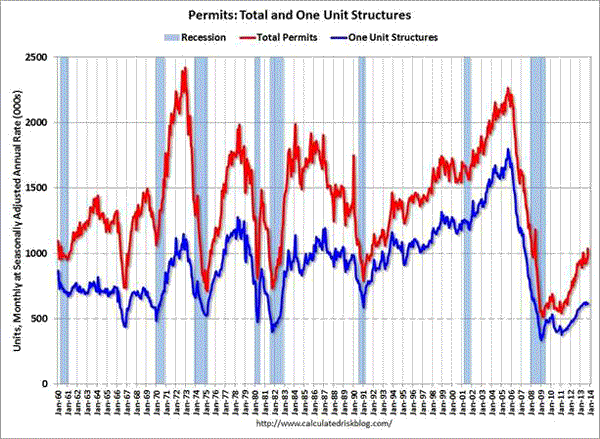

Source: Calculated Risk.

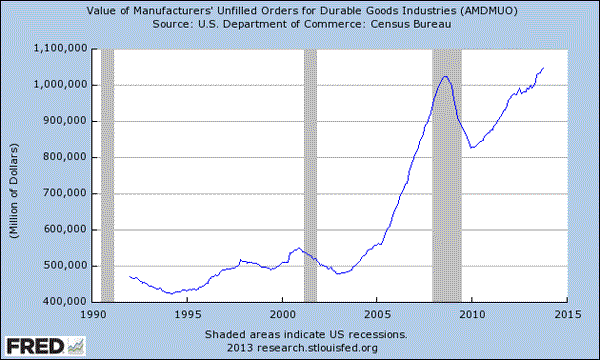

The most recent data on new housing permits and unfilled orders for new durable goods also paint a picture of a recovery that continues to gain momentum.

Source: Calculated Risk.

Source: FRED.

To sum up, the true growth rate of the U.S. economy was probably less than 3% for the third quarter, but could turn out to be above 3% for the fourth quarter.