In my last post, I valued Twitter (TWTR) at about $10 billion. I made a ton of assumptions to get to that value and I argued that changing those assumptions could give you a different value. In the last few days, I am sure that you have seen many stories about Twitter’s post-IPO worth, with numbers as high as $25 billion being offered as estimates. In fact, the gambling markets have already opened on the offering price and the players in that market seem to be siding with the higher numbers. As an investor on the side lines, I don’t blame you if are probably completely confused about these competing and divergent numbers but there is a way in which you can start making sense of the process.

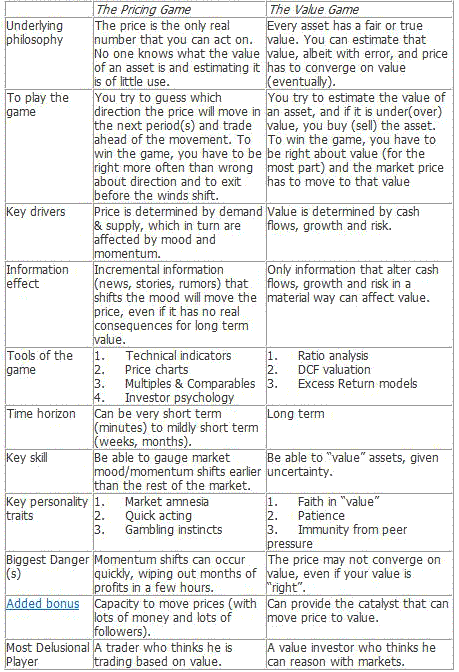

To set the table, I am going to go back to a theme that I have harped on before in my posts and that you are probably tired of hearing. When talking about investing, we often talk about “value” and “price” as if they are interchangeable, but they are not. In fact, in my post two weeks on Twitter, prior to its financial filings, I tried to price the company (as opposed to valuing it) and came up with a wide range of numbers, depending on my scaling metric (users, revenues etc.). That confusion between value and price lies at the heart of why it is impossible to have a conversation of how much a stock is worth, when the parties to the conversation come from different camps. So, to decipher the difference, I decided to go back to basics and tried to lay out the differences between the pricing game and the valuing game, as I see them.

The Pricing Game versus The Value Game

If you play the pricing game, you are a trader, and if you play the value game, you are an investor. I am not passing judgment, when I make this statement, because unlike some value investors, I don’t view traders as shallow or somehow less critical to the functioning of markets than investors. After all, a trader who makes a million dollar profit can buy just as much with that money as an investor who makes the same profit. Ultimately, which avatar (price or value) best fits you will depend not only on your level of comfort with the tools (Are you better at reading charts or valuing companies?) but also on your personal traits. In my experience, naturally impatient people who are easily swayed by peer pressure almost never succeed as value players and excessively cerebral folks who have to weigh everything in the balance, before they make decisions, are incapable of being traders.

This black and white view of the world may strike as some of you as extreme. After all, why not allow for shades of grey, traders who are interested in value and investors who think about the pricing process? While I will dive into this netherworld in future posts, I will not in this one, for two reasons. The first is that many of self-proclaimed hybrid investors are nothing of that sort. There are traders who pay just lip service to value, while using it back their momentum plays and investors who claim to respect markets but only until they start moving in the wrong direction. The second is that there is a danger in playing on unfamiliar turf: traders who delude themselves into believing that they understand value can undercut their own effectiveness just as much as investors who think that they can get in and out of markets, when it suits them. A healthy market needs both traders and investors, in the right balance. A market that has no traders and all investors will have no liquidity and one that has all traders and no investors will have no center of gravity. Ironically, each group needs the other for sustenance. Trading and momentum cause prices to move away from value, creating the bargains that investors try to exploit, and in the process of exploiting them, they create the corrections and momentum shifts that other traders exploit.

This, of course, brings me back full circle back to Twitter. If you are a trader, ignore almost everything that I said in my valuation post but do pay some attention to my pricing post. Even if you believe that my valuation assessment of $10 billion is a reasonable one, that should not stop you from buying the stock, even if it is priced at $20 billion, if you think that the market mood will take it higher. If you are an investor on the other hand, considering adding Twitter to your investment, it matters little how much hype or momentum underlies the stock. If your assessment of value is close to mine, it is not a good investment for you at a price higher than that value. As you listen to the debates about Twitter’s worth in the next few weeks, recognize that if the argument is between an investor and a trader, they are talking past each other. Stealing from the title of the bestseller from a few years ago, if traders are from Venus, investors are from Mars, and if one is talking about price and the other about value, they may both be right, even with vastly different numbers. Twitter can be a good trade and a bad investment at exactly the same time