In a new post, Steve Waldman suggests that the inflation of the 1970s was not a monetary phenomenon. I have two issues with Steve’s post. One is that (in my view) he is actually arguing that it was a monetary phenomenon, but he characterizes the argument differently from the way I would. That is, he suggests the monetary stimulus was done for a reason; to prevent high unemployment. In his view that made it a non-monetary phenomenon. I recently criticized a Matt Yglesias post on the same grounds. He had claimed hyperinflation was not a monetary phenomenon, because the expansionary monetary policy was done for a reason (monetizing debts.) Of course by that logic fiscal stimulus did not boost the economy in the early 1940s.

But there is another problem with the Waldman post. The monetary stimulus that was applied was far in excess of what was needed to prevent high unemployment during the 1970s.

The easiest way to see this is to imagine a scenario where Waldman was right. Suppose the Fed was targeting nominal wage growth, in order to maintain stable employment. And let’s assume that productivity growth slowed in the 1970s, which it did. Then Steve would have a point. Real wages would have to fall, and that would occur through higher inflation (since the path of nominal wages is stable, by assumption.) In that case a very reasonable policy of nominal wage rate targeting would lead to higher inflation during low productivity periods such as the 1970s, just as Waldman hypothesized. So it’s not a bad theory.

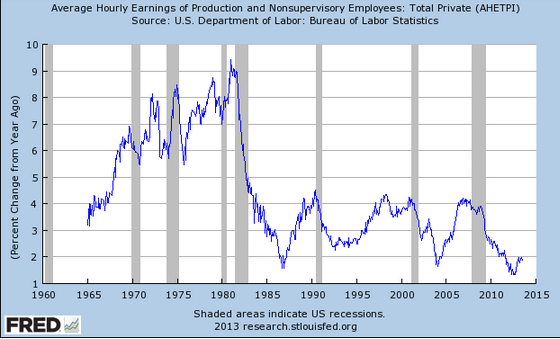

The problem is that he didn’t investigate the theory deeply enough. Something can be qualitative correct, a nice story (story in the best sense of the word) and yet still not have enough power to explain the data. And the big problem with Steve’s story is that the Fed did way too much stimulus, even if they were trying to stabilize the path of nominal wages. Here’s the average growth rate in the wage rate starting in January 1964:

This led to the famous shifting Phillips Curve phenomenon, which (after a lag of a few years) completely negated the effects of steadily higher (wage) inflation.

Still, I’d like to end on a positive note. There are some theories that help us to understand why the Fed blew it in the 1966-81 period:

1. Assumption of stable Phillips Curve.

2. Mis-estimation of the natural rate of U, which was rising.

3. Confusion between nominal and real interest rates.

Waldman’s theory deserves to be added to that list. It’s not the whole story, but it’s a significant piece of the story. Note that wage growth peaked at 9%. That’s a better indicator of the size of the Fed’s error than inflation, which peaked at over 13%.

PS. I seem to recall the original Phillips curve was done with wage inflation, before evil American economists (Samuelson?) switched it over to price inflation. Big mistake.